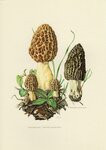

One of the most coveted edible mushrooms in the world is the odd-looking Morel.

I remember first seeing them as the poster child for the Sierra Club or on nature calendars and wondered what the heck they were? Morels don’t have gills. They look like pinecones. They don’t look particularly edible, they almost look dirty, yet everyone is always talking about them as a coveted prize.

Well, morels do deserve their reputation and they add a flavor to sauces slathered over meat that is impossible to duplicate. In fact, “Steak and Morels” is the “national dish” of my family served for most every birthday celebration or family gathering.

Morels are part of a large group of “Cup Fungi,” which means that instead of allowing their spores to drop off the sides of their gills, they actually eject them from the inside surface of their cups. When conditions are right, they eject them at speeds as fast as a bullet from a gun, though they don’t travel further than a few millimeters until the wind takes over. Cup Fungi are technically part of a group called ‘ascomycetes’ which includes fungi that literally look like a small cups, as well as yeasts [think beer and bread], penicillum, odd black things called Dead Man’s Fingers, mildews, truffles and even the fungi trapped inside of plants which comprise what we call lichens. They are the largest group of fungi in the world with over 64,000 species.

Finding Morels is a painful effort for some, particularly on the east coast where they are few and far between. They prefer the limestone soils of western Massachusetts, often associated with dead or dying elms, poplar, cottonwood and fruit trees, particularly apple trees. They associate with decaying trees because they are saprobic, meaning that they extract sugars by breaking down the lignin and and cellulose of trees.

Sometimes Morels will pop up here on Cape Ann, particularly if you put west coast cedar chips on your planting beds during the previous year. You could see dozens of them if you’re lucky. The other, more famous mechanism for fungi, of which they are not a part, is the symbiotic one called a ‘mycorrhizal relationship’ where fungi extract minerals from the soil and share them with the trees who, in turn, share the sugars they produce with the fungi. I use the term ‘share’ here loosely. The patterns of their fruitings are similar in the East as well as in the Midwest where, for example, Michigan has famous Morel festivals every year.

Morels fruit differently in the western states, however, and that is where I am headed in just a few days for my annual morel hunt. The well-known pattern there is that they fruit the year following a forest fire, so the hunt for them is often dirty and a bit depressing, depending on how severe the fire was. The theory is that they fruit intensely because their host trees have died and that activates them for one last feeding, so to speak. One can often find 20 to 30 pounds a day per person if the conditions are right. Then the problem becomes how do you dry them to get them home and we have all sorts of techniques for field drying. Their flavor is greatly improved if you dry them, then cook with them too. That is counterintuitive to people whose hunch is that cooking fresh Morels will be delicious. Fresh morels simply have a less intense flavor. The kingdom of fungi is full of surprises and functions differently than the plant kingdom.

Morels out West can also heavily fruit if logging occurred the previous year or along scarified soils along seasonally flooding rivers as well as occurring naturally where none of the trees died the year before. They are mysterious. When hunting a burn or disturbed area you have to thoroughly cover the area because they may not be fruiting in one part of a burn, but they could be so intense you crawl on hands and knees for hours in another. So, you have to hike with some intention, covering large, often steep, terrain to get to know what is happening in a given area.

That is the art of most any mushroom hunting. It’s a guessing game as to where they are and we often say jokingly “Morels grow precisely where they grow, and they never, ever, grow where they are not growing.”

Gary Gilbert lectures about fungi locally and through the Boston Mycological Club. Some of his recipes will be featured in the soon to be released Fantastic Fungi Community Cookbook, a compendium of recipes from myco-chefs throughout the country.