The towns of Manchester, Essex and Hamilton have signed onto a national class action lawsuit against 13 manufacturers of toxic “forever chemicals” in an effort to mitigate the tens of millions of dollars in expected costs to remove these chemicals from municipal water supplies.

The lawsuit is being led by New York law firm Napoli Shkolnik representing municipal property owners, state attorneys general, water providers, and exposed and injured individuals. As Attorney General in 2022, Maura Healey signed Massachusetts up for the Napoli suit as one of the first states (along with Ohio, New York and others). Then, KP Law, which serves as town counsel to about a third of the state’s 347 municipalities, partnered up with Napoli to bring many of its clients—including Manchester, Hamilton, and Essex—into the fold.

It’s not yet clear what, if anything, smaller municipalities like Manchester, Essex and Hamilton will get if the lawsuit is successful. Figuring that out could take years, and in the meantime, towns are realizing that mitigating PFAS in local water supplies will be both extensive and expensive.

The Napoli lawsuit is a contingency case, which means the firm will collect (25% of the total settlement plus costs) only if it succeeds against the 13 manufacturers (which include 3M, Dupont, and others) targeted in the lawsuits. KP Law would collect a cut of Napoli’s fee.

In October 2021, Manchester began regular PFAS testing at its municipal wells at Lincoln Street and Gravelly Pond. The following year, Manchester formed the Water Resources Protection Task Force to study the quality and quantity of town water resources. After 18 months, the task force completed its mission and in a June report it recommended a new water rate structure and flagged PFAS mitigation as a critical issue.

Back when the task force began its work, the US Dept. of Environmental Protection’s standard for acceptable PFAS levels was relatively high—70 parts per trillion (ppt)—while Massachusetts’ DEP dictated a more stringent standard of 20ppt, which is the equivalent of a grain of sand in a swimming pool of water. PFAS testing at the Lincoln Street well has consistently come in between 10ppt and 20ppt, and Gravelly Pond has registered below 10ppt.

But this last March, the EPA came out with a sobering new standard, dropping from 70ppt to just 4ppt. Towns have three years to comply, which means installing industrial-grade carbon filter systems that must be operational by 2027.

When the new EPA numbers were announced, Manchester’s Dept. of Public Works had already crafted a PFAS mitigation strategy. It recommended augmenting the water treatment plant at Gravelly Pond with the new carbon filters and then transporting water from the Lincoln Street well up to Gravelly Pond to be treated together.

Two weeks ago, DPW Director Chuck Dam told the Manchester Finance Committee the PFAS mitigation plan would cost an estimated $25 million, which includes installing the carbon system, treating water at Lincoln Street and Gravelly Pond, and installation of the connecting pipes between Lincoln Street and the upgraded water treatment plant at Gravelly.

Dam also said demand for the carbon filter systems would likely spike nationally for PFAS mitigation equipment and consulting, which could impact costs for both.

PFAS gets its name from perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl and they’re called “forever chemicals” because they accumulate in the body and the environment over time. PFAS has been associated with firefighting foam used at military bases and airports, non-stick cookware, weatherproof performance fabrics, food packaging, and stain-resistant home textiles.

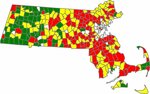

Approximately 126 public drinking water systems in Massachusetts are said to have significant PFAS levels, with 86 communities having “severe concentrations.”

The class action is about securing funds to clean up and remove, restore, treat and monitor PFAS contamination. It’s also requesting an order requiring the manufacturers to reimburse the state for the damages the products caused.

It’s not clear how monies that come to the state would be divvied up by the towns, especially when municipalities like Hyannis and Acton have PFAS levels that far exceed most other municipalities. The claims are being made under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, the Massachusetts Consumer Protection Act and the Massachusetts Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act.

Municipal water supplies are heavily regulated by both federal and state environmental divisions. Retail bottled water is seen by some as a safer alternative in light of PFAS, but experts warn that bottled water companies are not required to test for or report PFAS in its product, and they’re regulated by the federal Food & Drug Administration, not the EPA.

Class action lawsuits are a legal mechanism that enables a large group of individuals – known as a class – to collectively seek compensation or remedies for a shared grievance.

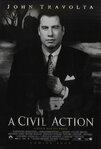

To some, they are controversial. Certainly, they are fodder for popular books and movies like Erin Brockovich, or, better yet, the Oscar-nominated movie (and best-selling book), A Civil Action about Beverly attorney Jan Schlichtmann’s dramatic quest to find justice for a Woburn, Mass. neighborhood of working families impacted by a bloom of cancer allegedly connected to groundwater contamination.

But class action lawsuits have proven to be a highly effective tool for state governments seeking to recoup public health-related expenditures. Massachusetts was a pioneer of this approach in the 1990s when a young state Attorney General, Scott Harshbarger, took on Big Tobacco as part of a then-novel strategy to use a class action to recover financial impacts related to smoking. That ended in an historic $9 billion national settlement.

Nearly 30 years later, that strategy is no longer “novel.” In fact, class actions tied to recovering taxpayer money are getting increasingly common, seen in everything from sugary drinks to opioids.

In fact, according to Bloomberg Law analysis, there were 40 PFAS lawsuits from 2005 to 2011. By 2022 there were more than 6,400 and part of the class action legal process these lawsuits are streamlined behind main, or “lead” cases. (Napoli’s is one of them). 3M Corporation in Minnesota, which developed its firefighting foam with the US Military decades ago, is the top target of the lawsuits. Dupont is a close second. For both, these lawsuits are triggering an existential crisis.

On one side, class action lawsuits like this one that Manchester, Essex, and Hamilton are signed up for are a testament to the power of collective action in pursuing accountability. This is critical, especially for individuals, states, and towns that otherwise simply can’t stand up to corporations that have the advantage of massive budgets, connections and staying power.

Others criticize the increasingly sophisticated use of “multi-district” litigation strategies (which class actions are now termed) with simultaneous coordination of thousands of litigants across many states. They say class actions amount to corporate shakedowns, where attorneys stand to be the biggest financial winners, often leaving their clients to share the crumbs.