Last week the Manchester Finance Committee reviewed a proposal that would cut Manchester’s savings rate from 15.86% to 6.05% by using a new formula that removes Manchester’s portion of the regional school district budget before setting its reserve rate.

The proposal—offered by FinCom Chair Sarah Mellish—would calculate Manchester’s total reserve funds from a baseline of $20,705,473 after removing the town’s share of the school district budget and adding in capital and OPEB (“other post-employment benefits”) instead of using the state certified town budget, which is $34,668,705.

Mellish said the new calculation would free up money locked in the town’s coffers, enabling it to be applied to other obligations or be returned to taxpayers in the form of lower tax rates in future years.

Based on FY23 data, Manchester holds $5,497,420 in two state-certified reserve funds—$1.879 million in the MBTS “Stabilization Fund” and $3.617 million in what’s called“Free Cash.” Mellish’s proposal targets $2.1 million between both funds, which is 6.05% of MBTS’ FY23 annual budget, 5.3% of the FY24 annual budget, and by the new math, would be 10% of the lower base in Mellish’s proposal.

“At the end of the day, we would be going from 10 percent down to 5 … which I’m in agreement with,” said FinCom member Mike Pratt.

“I don’t think we want to voice it that way,” Mellish said, offering revised messaging. “I think we want to voice it that we’re still doing the 10 percent, but (after) excluding the school budget and adding in annual capital expenses.”

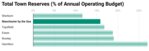

If adopted by the Select Board, Manchester would stand out among comparable towns in calculating reserves.

For instance, Hamilton’s annual budget ($35.449 million) is similar to Manchester’s ($34.668 million), and, like Manchester, Hamilton is part of a regional school district. Yet Hamilton holds 27% of its budget in reserves that are tied to a list of large, planned initiatives. According to Finance Director Wendy Markiewicz, Hamilton does not back out regional school district monies before calculating reserves.

Similarly, in Rowley ($22.8 million budget and part of the Triton School District) holds 19.04% in combined reserves. Sherborn ($30.588 million budget and part of Dover-Sherborn School District) keeps 11.64% in combined reserves. Topsfield ($32.8 million budget and part of Masconomet Regional School District) has 16.8% in reserves. None of these municipalities calculates reserves after backing out their share of the annual school district budget.

The concept of “reserves”—how much should go into them, how and when to spend them—has taken a lot of attention this year.

During the last four ME Regional School District annual budget cycles, the school committee had to bridge gaps in its operating budget by pulling from district reserves, prompting criticism that doing so threatens its bond rating. Then, reserves emerged during Town Meeting debates over capital funding for new turf fields on Lincoln and Brook Streets. Why not use the money we have on hand instead of raising taxes, some voters asked?

In all these, there’s been a “black box” quality to discussing reserves. What are they, how do they work in municipalities, and do they even matter in a wealthy town like Manchester that can easily approve expensive projects and capital items without leaning on accrued savings?

Put simply, reserves are just regulated municipal savings accounts. There are two types—Free Cash and Stabilization Funds—and every year the Massachusetts Dept. of Revenue (DOR) certifies them. Free Cash is like a family savings account. They are unrestricted and available to appropriate by a majority vote at Town Meeting.

Stabilization accounts, on the other hand, are “rainy day” reserve funds that carry balances from one fiscal year to the next, and can only be drawn on after a 2/3 vote at Town Meeting. They’re hard to tap because Stabilization Funds are supposed to be used for specific initiatives, emergencies, or to avoid borrowing for a capital project.

“A sound stabilization policy will set a schedule of annual appropriations designed to gradually reach and sustain the target balances over time,” according to the Mass Dept of Revenue. (Over the past 10 years this is what Manchester has done.)

During School Committee budget season, the FinCom’s Mike Pratt researched the state’s AAA bond rated municipalities and their levels of Free Cash. He reported that savings rates varied wildly from 2.96% (Ashland) to 9.21% (Topsfield). Could Manchester lower its savings rate and retain its coveted AAA bond rating? Pratt’s simple answer is yes. More than that, Pratt’s answer is that bond ratings are about more than Free Cash balances.

And it’s true. Pratt’s analysis lacked half the data, specifically each town’s Stabilization Funds, which also can vary greatly based on a town’s long-term goals, and savings philosophy.

The lowest Free Cash level in Pratt’s reserach was Ashland, with just 2.96% in that form of reserves. But Ashland also has a certified Stabilization Fund of 11.7%, which brings its total reserves to a robust 14.66%.

And Topsfield’s 9.21% Free Cash rate is certainly higher than Ashland’s (and lower than Manchester’s), but by adding its 7.61% Stabilization Fund, Topsfield’s total reserves are relatively large, 16.8% which is actually larger than Manchester’s 15.86%.

So, what of the idea that AAA ratings aren’t necessarily related to strong levels of savings? Manchester holds a AAA bond rating. Would its rating be threatened if it cut reserves in half?

According to bond rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch, factors like financial management, economic fundamentals, debt and liabilities, and demographic indicators all figure into bond ratings.

But as important as financial management is behavior. Transparency of policies and reporting factor into ratings. So does planning, or establishing appropriate long-term goals for infrastructure and capital projects. And avoiding debt and liabilities.

In the end, it’s about fostering confidence in growth and stability that trumps all, and that translates into long-term consistency and avoiding sudden or disruptive moves. So, towns will choose to create savings accounts for big-ticket items, like the Manchester Fire Engine Fund (which plans 10 years out for a $1.5 million acquisition).

“The organizations that have good policies and are well managed consistently are the ones that are going to navigate successfully,” said Northborough Town Administrator John Coderre, whose municipality won the national Government Finance Officers Association’s award for best practices.

Capital Projects in the Wings

Whether it’s the school district budget or Manchester’s municipal budget, reserve funds of any type today offer support for two things: capital projects, and inflation. After all, healthy reserve funds enable planning for big items in the future, they demonstrate the ability to put skin in the game when it comes to borrowing for big initiatives, and they act as a safety net during economic downturns or unexpected expenses.

Ann Harrison, Select Board chair, stood in defense of holding strong reserve funds during May’s Annual Town Meeting when residents had to weigh whether to bank (as reserves) a $400K “refund” from the school district or lower the tax rate by 1.3% (130 basis points). The Select Board supported bolstering reserves. The FinCom’s position was for the lowered tax rate. Harrison, a committee veteran who has served both as Chair of the FinCom and for years as a member of the School Committee, told voters that Manchester faces a significant list of capital projects. A desperately needed DPW headquarters. Upgrades to the Manchester Water and Sewer Treatment Plants. A Senior Center. A new Essex Elementary School, just to name a few. Harrison also said she remembers back ten years ago when Manchester’s reserves were alarmingly low and its AA2 bond rating reflected it.

But Harrison also told voters she remembered a time when Manchester’s reserves were low, and it was hard when there was a hard economic shift (driving excise and real estate tax income down). That, she said, is what reserves are for.

Last week, Mellish signaled a different point of view. She said Manchester doesn’t use its Stablization Fund, and besides, voters will accommodate the big capital projects on the horizon by simply voting the pay for them at Town Meeting when they are asked. The town, she said, should not be warehousing money (at little to no interest, added Pratt) that stays untapped when taxpayers would rather have that money back in their pockets.

The FinCom will continue to review its proposal.