They spawn in the freshwater estuaries of Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and the Hudson River and then migrate north to Cape Ann waters and beyond. The “schoolies” begin arriving in May followed by the bigger fish in June. By late September the pattern reverses as they head south to over-winter in warmer waters.

Whether fishing with spin tackle using bait or artificial lures or a fly rod, fishermen revel in the experience of hooking into a striped bass. “They hit like a ton of bricks” (as my father used to say) and put up a spirited fight. I’ve fly fished all over the world—Alaska, New Zealand, Patagonia, Mongolia—yet some of my most memorable fishing experiences have been right here in the Essex River Estuary and along the coast between Manchester and Gloucester.

Unfortunately, fishing around here has been a disappointment the last couple of years. Just ask the fishing guides. Dave Rimmer is a wildlife biologist who has been guiding fly fishing and light tackle trips for stripers in the Merrimack and Plum Island area for decades. In recent years, he said, “it’s been tough to be a guide. I’ve had a couple of days where I’m thinking ‘where are the fish?’”

Skip Montello of Rockport is a catch-and-release-only guide who’s fished the waters around Cape Ann for decades. “We didn’t see many big fish last year,” he told me. “We only caught one fish over 40 inches the whole season!”

As thoughts turn to the summer fishing season, local fishermen are wondering whether the downward trend of the last couple of summers will continue. It’s a concern shared up and down the East Coast. As Dave Rimmer puts it, “We’re on the downside of the curve and hoping to see the numbers start climbing back up again.”

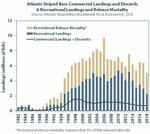

The curve Dave is talking about is illustrated by the “Atlantic Striped Bass Commercial Landings and Discards & Recreational Landings and Release Mortality” summary. These data are updated every year by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), which coordinates management and conservation of fisheries within three nautical miles of the coast for 15 states from Florida to Maine.

In the 1980s the striped bass fishery was in bad shape due to overfishing and industrial and agricultural pollution in the breeding waters. In 1984 Congress passed the Atlantic Striped Bass Conservation Act, requiring all states to comply with the ASMFC management plan. As a result, a moratorium was placed on striped bass fishing in the Chesapeake, while catch limits and size restrictions were instituted by all states. The moratorium was lifted in 1990 but catch and size limits remained in effect. And, so began the glory days of striped bass fishing around here. “In the mid 90s and early 2000s … it was just off the charts,” Rimmer recalled.

The number of recreational striper fishermen has increased dramatically since the early 1990s, and so has the mortality they’ve caused. In 2006 alone, recreational fishermen on the East Coast landed over 4 million “keepers,” while, at the same time, an additional 4+ million fish died after release. Over the last decade, commercial fishing has accounted for about 10 percent of the overall mortality.

But overfishing isn’t the only problem. Down in the Chesapeake, the source of approximately 70 percent of Cape Ann’s summer striper population, the percentage of fry that survive their first year can vary dramatically. Fishery managers refers to this as “recruitment.” A good recruitment year is likely to produce a good breeding stock seven to eight years later. Low recruitment from 2005 to 2010 is a major factor in the lower number of breeder-sized females caught in Massachusetts in recent years.

Each coastal state interprets the guidance of the ASMFC and sets its own regulations, which vary considerably from state to state. For example, it is illegal to sell striped bass in Maine, New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. And while most states allow rod-and-reel fishing only, Delaware, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, and Virginia still allow commercial fishermen to use some form of netting, a practice commonly criticized for its indiscriminate harm to other marine species, not to mention the stripers.

In Massachusetts, fishing regulations are established by the Department of Marine Fisheries (DMF). Starting in 1990, the size limit for a “keeper” in Massachusetts was set at 28 inches. A female of that size would be six or seven years old and just at the beginning of her egg-laying years. Stripers can live more than 30 years. The larger the female—and pretty much all stripers over 30 inches are female—the more eggs she is capable of producing. Retired educator and Essex River guide, Kalil Boghdan, says that a 15-year-old female would likely be 44 – 45 inches and capable of producing three million eggs, six times more than a 28-inch fish.

New regulations for Massachusetts are in effect for 2020. According to Mike Armstrong, Assistant Director of the Mass DMF, the new regulations are intended to reduce catch mortality and protect the most fertile large females. The most consequential change is the new “slot limit” for recreational fishermen. A “keeper” is now a fish between 28 and 35 inches.

Skip Montello isn’t crazy about the new regulations. “The commercial guys are going to target all the breeder fish. It’s not their fault. The regulations say they can do it. But we should be leaving the big breeder fish alone.”

Commercial fishermen don’t necessarily disagree. Al Williams was born “on the island” (i.e., Gloucester) and has fished these waters for over 50 years. One area fisherman said “if there is a ‘Great White Hunter’ of Cape Ann striper fishing, it would be Al.” Al told me “the spawning stock biomass is in trouble. We need the big breeder fish in high numbers to sustain the fishery.” And what about the new 35-inch minimum? “The jury is out as to whether that’s a prudent thing to do. Maybe we should be fishing in the same slot limit that folks are fishing recreationally.”

According to Mike Armstrong, about 4,700 commercial fishing permits were issued in 2019, but only about 1,100 reported catching any fish. Moreover, commercial fishermen missed the state quota in both 2018 and 2019, and the 2020 quota has been reduced by 18 percent. So, is commercial fishing really that big of a problem?

Some argue that many commercial fishermen are really just recreational fishermen in disguise. For example, I could purchase a commercial fishing license for about $160—a very low barrier to entry—and that would allow me to take 30 fish a week over 35 inches. And on the five days that I’m not a “commercial fisherman” I can go back to recreational fishing.

This is one reason “Stripers Forever,” a non-profit conservation organization, advocates for the striped bass to be designated a “gamefish,” putting an end to commercial fishing on the Atlantic Coast. They contend that commercial striper fishermen are mostly made up of what they call “recremercial” fishermen, not people whose primary source of income is based on the striper fishery.

Fred Jennings, a Stanford-trained economist and co-chair of the Massachusetts chapter of “Stripers Forever,” thinks fisheries management focuses too much on the value of striped bass as a market fish, while underestimating the market value of recreational striped bass fishing in its totality. He makes the case that there is a $1 billion industry for recreational striped bass fishing in Massachusetts alone, and he’s more than happy to share the mathematical models to support his contention.

So, what’s the of the commercial market for locally caught striped bass? In a word: limited. Not many local restaurants include striped bass on their menus. Romeo Solviletti, General Manager at Steve Connolly Seafood in Gloucester, told me the supply has been low the past couple of years. When he does have it, his primary wholesale clients are high-end restaurants, hotels, and casinos.

Debate about striped bass fishing regulations may never end, but it’s important to keep in mind the sheer volume of fishing pressure from recreational fishermen compared to commercial fishermen. Dave Rimmer, Fred Jennings, and Kalil Boghdan all agree that the new “slot limit” is a step in the right direction. “It’s great that those really big females are now going to be released,” Rimmer told me. But there’s no denying the striped bass fishery has been trending in the wrong direction. If this trend continues, more drastic measures will be required to protect the fishery and avoid another crash.